Salters’ Stories: Ann Hubbard

Ann Hubbard went from the chemistry industry into inspiring teacher across the UK and the world. Her efforts were recognised with a Salters' Teacher Award,

Ann Hubbard worked in the chemical industry for many years before progressing into teaching. She has inspired thousands of young students through practical experiments, which she delivered both in the UK and abroad. All the incredible work Ann did earned her a Salters’ Teacher Award, which ran from 1993 – 2004.

You are one of our alumni, having won one of our Salters’ Teacher Awards. How did you hear about this award?

Salters’ Teacher Prize ad.

The Salters’ Institute sent the information to the schools, and my husband told me to enter. I remember saying, “Rubbish, I’m not good enough for that award,” but to my surprise I got it!

I recall that the award was established by Lord Porter to celebrate the Salters’ 600-year anniversary. I still have the photo of me and Lord Porter when I went to the Award Ceremony.

How did you get into chemistry?

I have always been a chemist, and that started at school due to an excellent teacher, which in my experience is how nearly all chemists find their passion. A good teacher is invaluable. I went to a Girls’ Grammar school that didn’t have strong science numbers. I think only four of us went to university from my year group in total actually. I mean we are talking the 1950-60s here.

But I applied for University of Manchester as they had a new professor and he wanted to build the chemistry department.

I did a first degree there, and actually met my husband while at university. We got to know each other as undergraduates; he was also studying chemistry. We then got engaged after we finished our degrees. We never had any money, so we decided that we both needed to get a job. This led me to work at ICI Pharmaceuticals (which is now AstraZeneca). My boss, who had just finished his post-graduate award in the States, was Peter Doyle (Master Salter in 2003).

Although the job was good (I was working for a drug to treat arthritis), I found myself getting bored. So, I went back to my manager and asked about whether I could do my PhD. They agreed straight away and before I realised, I was doing my PhD back in Manchester. After this my husband got a job at Beechams Pharma in Brockham, and I got a job with ICI Pharma Head Office in London, because we were living in Redhill at the time. When Beechams found out I was with ICI they offered me a job with them because, of course, they wouldn’t want me working for a rival company.

There I was in the patent protection department which was really interesting. If they thought that somebody was invading their patent, I had to try to chemically prove it for [the patent] to stand up in court, that they were infringing [their patent].

What led you to teaching in secondary schools?

Well, my husband went into teaching first after getting a job at a London college as a Physiology lecturer. They wanted someone to teach Physiology. Later he got another job at Surrey University as an Immunologist —that’s what his research was, and that’s what he did until he retired.

While there he got his job teaching chemistry in schools with the London authority scheme, and I remember him saying to me, “I get school holidays with this job. Why don’t you consider it?”

I did love my job with Beechams, but I decided to give it a try.

So, just like that, I walked out of the lab and into a boy’s comprehensive in Guildford to teach chemistry. Apparently, the school put a book on me as they didn’t think that I would survive long as it was considered a ‘rough school’. I stayed for a really long time, however, until a job at Dorking Grammar came up, which was closer to home.

Four years later the job at Reigate College came up as the Head of Chemistry, which is where I stayed until I retired. The problem there was that it was fairly new and had a very small chemistry department (only 12 A-level students if I remember rightly). They said my job was to expand it.

Have you notice a change in chemistry education over the years?

Not massively while I was teaching, but I’ve been retired for 15 years. I do know it is dire now, because the son of my former work colleague is head of a large comprehensive and he has had terrible trouble trying to find chemists to teach A-levels.

I wish people knew how uplifting it is to watch students enjoy chemistry! I have tried to get chemists to get involved in school outreach but not many have been responsive. I mean I have all these resources, and I feel if they could see the way students react during these workshops they would want to get involved.

How do we encourage bright chemistry graduates to go into teaching?

I think one of the problems is the A-level syllabus. I don’t want to get political, but government interference had negatively affected the A-level syllabus. The other thing that happened was the amount of paperwork you had to do went up, which took the joy out of the work. Admin is becoming too intense for teachers. The paperwork and admin are the evidence of teaching becoming more bureaucratic, coupled with the fact that it’s not well paid. I’m not entirely sure how we resolve this in order to bring chemists into teaching, but you can understand why people are leaving.

The only solution I can think of is if you could provide support material to non-chemists who have had to teach chemistry. I can imagine that the heads would appreciate it, as they could make it a condition of employment that they could take a course (or use the material).

Something else I couldn’t have done without were the technicians. They were a huge support in practicals.

How did you start your impressive outreach work with schools?

So, if we go back to Reigate, where I was trying to increase numbers from my 12 students – I realised I needed to begin engaging students at a much younger age. My firm belief was that, if you wanted to get students into chemistry, you need to catch them at 10, 11, 12 years old, as I feel by GCSE and the 6th form they already have preconceived views. For this I went back to Beechams, as I knew the Director of Research there (actually, I taught his son!). I said to him, “I want to take a lecture out to the local schools, and I would therefore need liquid nitrogen, and solid CO2 to take with me to make it exciting.” Everything else we had in the labs.

He said, “Fine just let us know what you need, and you can have it. You will need a contact here, that’s the only thing.” I had an old work colleague there, John Hanson, so I called him and let him know what I needed and when I was coming to collect the items. He was great and got it all ready for me.

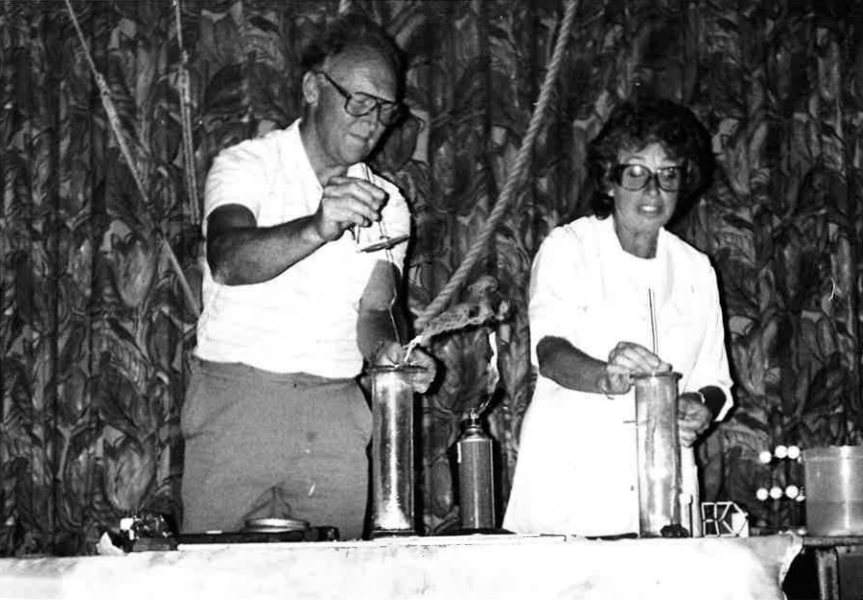

Ann Hubbard (right) and John Hanson (left) demonstrate a chemistry experiment during one of their outreach events. Courtesy of Ann Hubbard.

So, instead of teaching on Wednesday afternoons, I used to go out with this lecture to the local middle schools. It was a 40-minute practical workshop where I would show students chemistry experiments and talk through the reactions that were happening. I called it ‘Wizz Bang’ and would go back to the same schools every year to do it. In the end, we used to travel everywhere, me and John (with John doing the experiments, while I talked through what was happening). It started with local schools, then escalated to universities inviting us to do their outreach. The key thing always is showing students how exciting chemistry can be, because it is!

All this happened until I retired, because then I didn’t have access to a lab which made it much harder. I think the student A-level numbers went up to 120 pupils when I finished teaching though.

This enthusiasm from students really highlights the importance of practical experiments in schools, and how this links to the uptake of chemistry at A-levels and beyond. I feel this gap can be missing in the schools where teachers aren’t able to do experiments that demonstrate these exciting things, because either they haven’t seen them or been trained, or they don’t have resources and time.

I also understand that I was very lucky with Beechams being a huge reason that these lectures could happen — where they helped me bring chemistry to life. They would provide their staff, needed chemicals, sometimes even loaning a van if we were doing long trip lectures. They also used to offer tours to local students after they had done experiments with us, something other companies used to do as well. Sadly all these offerings have seemed to stop now. It’s a shame because it really allowed students to envision themselves there.

The Salters’ Institute feels inspired by Ann Hubbard’s story regarding school outreach. If you feel that your company would be able to support us in this work, please connect with our Awards and Alumni Programme Manager – [email protected].